“PRAYER & TRANSCENDENCE” now at Washington, DC’s Textile Museum

THE TEXTILE MUSEUM at the George Washington University Museum has organized a fascinating exhibition that explores the role and iconography of classic prayer carpets–a subject I knew nothing about, but which I enjoyed thoroughly under the guidance of a superb docent.

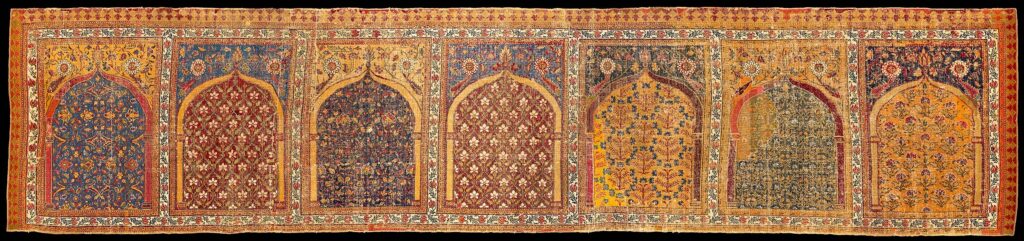

The exhibition displays 20 carpets from across the Islamic world, and covers the 16th through the 19th centuries. Textile Museum curators drew selections from their own collections along with historic examples from the Harvard Art Museums, the Cincinnati Art Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Markarian Collection. Senior Textile curator Sumru Belger Krody described how these textiles played “a critical role in creating, defining, and enhancing religious spaces–and their designs have connected cultures across time and place.” The imagery of an arch and flowers transforms such carpets from a simple textile into the embodiment of holy space–“a link between the earthly and transcendental realms where worshippers can commune with God.”

Above, right: Prayer & Transcendence exhibit at Washington’s Textile Museum. Photo by Cara Taylor/the George Washington University.

Prayer carpet iconography evolved over centuries, circulating through trade routes and religious pilgrimages. The carpets on display in the exhibition come from Turkiye, the Caucasus, Iran, Central Asia, and India. All share a common motif–an elegant arch surrounded by vegetation and flowers–with the arch representing the gateway to paradise, which the Koran conceives as a lush, walled garden.

Some of the most elegant carpets were woven in court or high-status workshops and feature “intricate designs and exquisite fibers that leave the viewer feeling like they’ve fallen into a garden.”

Muslim followers obey the Five Pillars of Islam, with the Second Pillar requiring that they come together five times a day to pray. Muslim prayer is a physical as well as a mental and spiritual act of worship, and represents a person’s most direct contact with God. Before entering the mosque for prayer, a person must perform a ritualistic washing. A prayer carpet prevents the worshipper from contact with the ground, and allows him to prostrate himself to touch his forehead to the ground while reciting verses from the Koran. The textile creates both a literal and a metaphysical clean environment for worshippers.

Below: “Saf” (multiple arch prayer carpet); India, Deccan Plateau, Warangal; late 18th century. The Textile Museum Collection R63.00.15. Acquired by George Hewitt Myers in 1950. Courtesy of The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum

Prophet Muhammed (570 CE – 632 CE), the founder of Islam and the proclaimer of the Koran, Islam’s sacred scripture, initiated the ritual of using a “Khumran,” a prayer rug made of palm fronds. Soon, other Muslim leaders began ordering carpets designed by great court artists, and the rugs became a symbol of power during the Ottoman (c. 1300-1923), Safavid (1501-1722), and Mughal (1526-1739) dynasties–all of which shared a common Turko-Mongolian Islamic heritage.

Prayer carpets can be woven of silk, cotton, or wool, and each has an Islamic mark embedded on the top–the “mihrab”–which shows the worshipper where to place his forehead. Prayer carpets have also showcased Islamic poetry and symbolism to convey religious thinking in figurative terms–a function that melds well with the use of prayer carpets as the sacred space for a worshipper to commune with God.

Left: Prayer carpet; Safavid Empire, Iran, Qazvin or Tabriz; 16th century. Metropolitan Museum of Art 17.120.124. Mr. and Mrs. Issac D. Fletcher Collection, bequest of Issac D. Fletcher, 1917.

One 16th century carpet in the exhibition is a rare example of the artistic style that flourished in the Ottoman Empire during the reign of Sultan Suliyman the Magnificent, who ruled the Ottoman Empire at the height of its power. The prayer carpet design illustrates a window into a magic garden of delights—of Paradise. (Metropolitan Museum, 1974.149.1) With another prayer carpet, the exhibition describes how Ottoman court art presented “the most profound contradictions between strict Islamic religious observances on the one hand, and the love of luxury objects and beauty on the other.” The example representing this dichotomy is a 17th century Ottoman prayer carpet decorated with designs of religious observance, but also with lush flora of sinuous leaves and exuberant lotus blossoms. (Textile Museum Collection, 1964.24.1)

Later carpets in the exhibition include a 19th century prayer rug from a village in Turkiye (Textile Museum Collection, 2006.19.2), and carpets that show how Islam and Judaism have shared a vocabulary of symbolism. The door-like forms given to the Muslim mihrab and the Jewish Torah Ark share artistic symbols, such as the arch and lamps that signify Divine Light for both religions. (Textile Museum Collection, R34.3.2 and R16.4.4), below, here.

Right: Torah Ark curtain; Ottoman Empire, Egypt, Cairo; early 17th century. The Textile Museum Collection R16.4.4. Acquired by George Hewitt Myers in 1915.

The GW Museum/Textile Museum docent who helped demystify the prayer carpets for me was Catherine Seibert. A weaver herself, Catherine made the arches, symbols, colors, and borders comprehensible. She told me that while all of the carpets have been woven in the service of prayer, individual carpets are “quite distinctive.” Some of the most elegant carpets were woven in court or high-status workshops and feature “intricate designs and exquisite fibers that leave the viewer feeling like they’ve fallen into a garden.” But as a weaver, she explained that she especially enjoys the prayer carpets woven by village women for their families’ personal use. They “sometimes incorporate small personal design elements, like a comb, into their colorful and exuberant designs.”

Pageantry, music, words, symbols, and ritual can take us to another place, whether religious or not. As this exhibition brilliantly conveys, prayer carpets are a perfect vehicle for a journey that transports us beyond the everyday.

By Amy Henderson, Contributing Editor

PRAYER & TRANSCENDENCE will be on exhibit at the George Washington Museum/Textile Museum through July 1, 2023. See museum.gwu.edu/prayer-and-transcendence.

Reader’s Bonus:

HEAVENLY THRESHOLD

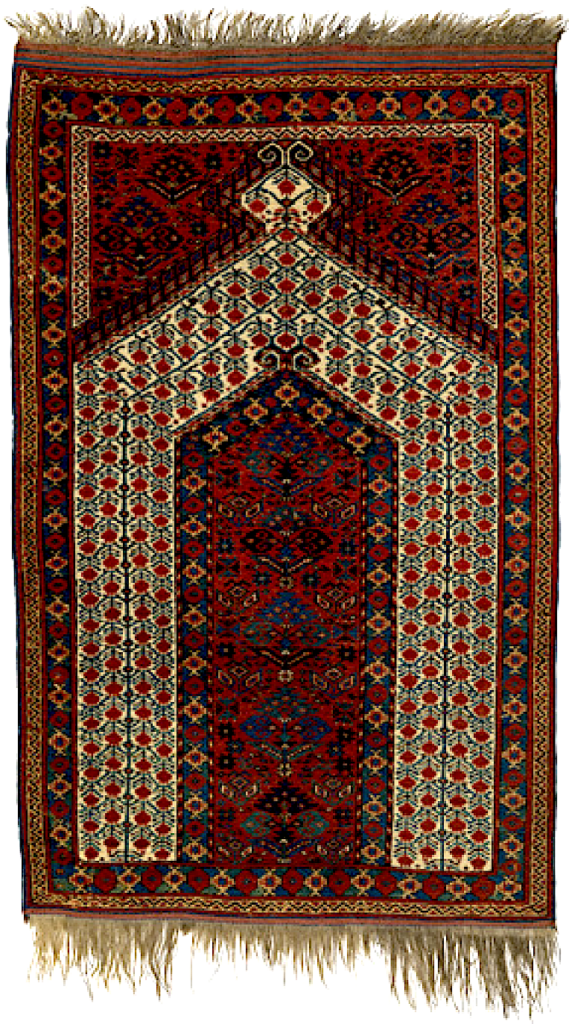

The most iconic image in a prayer carpet is the directional arch. The origin of this motif is an ongoing discussion among scholars. It might have been inspired by the “mihrab,” a niche in the wall of the mosque that indicates the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca, which believers face when praying. The niche can also be seen as the gateway to Paradise, open to believers with good moral standing.

In the Koran, Paradise is conceived as a lush walled garden with an arched gateway, a motif that became a powerful image in Islamic art. Prayer carpets frequently depict fl oral and vegetal decorations surrounding an arch, which are interpreted asmetaphors for Paradise.

Above, right: Prayer carpet; Central Asia,

Middle Amu Darya area,

Bukhara region;

19th century. Wool; knotted

pile, asymmetrical knot open

to right; 194 x 104 cm.

The Textile Museum Collection

1968.18.2.

Bequest of Arthur J. Arwine.