The Melancholy Soul of Tchaikovsky: A Cinematic Journey

Canadian born Hershey Felder, writer, actor, playwright, composer, and musician – piano is his forte – with some 5,000 one-man solos shows performed around the world since 1999, is known for creating historically accurate and exquisitely nuanced portrayals of world-famous composers. Among his extensive composers’ repertoire—each of which he brings gloriously alive—are musical greats Chopin, Beethoven, Debussy, Rachmaninoff, Puccini, Leonard Bernstein, George Gershwin, and Tchaikovsky. Many of these productions are available for purchase at www.HersheyFelder.net.

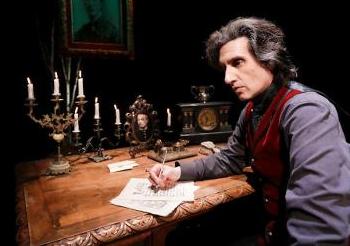

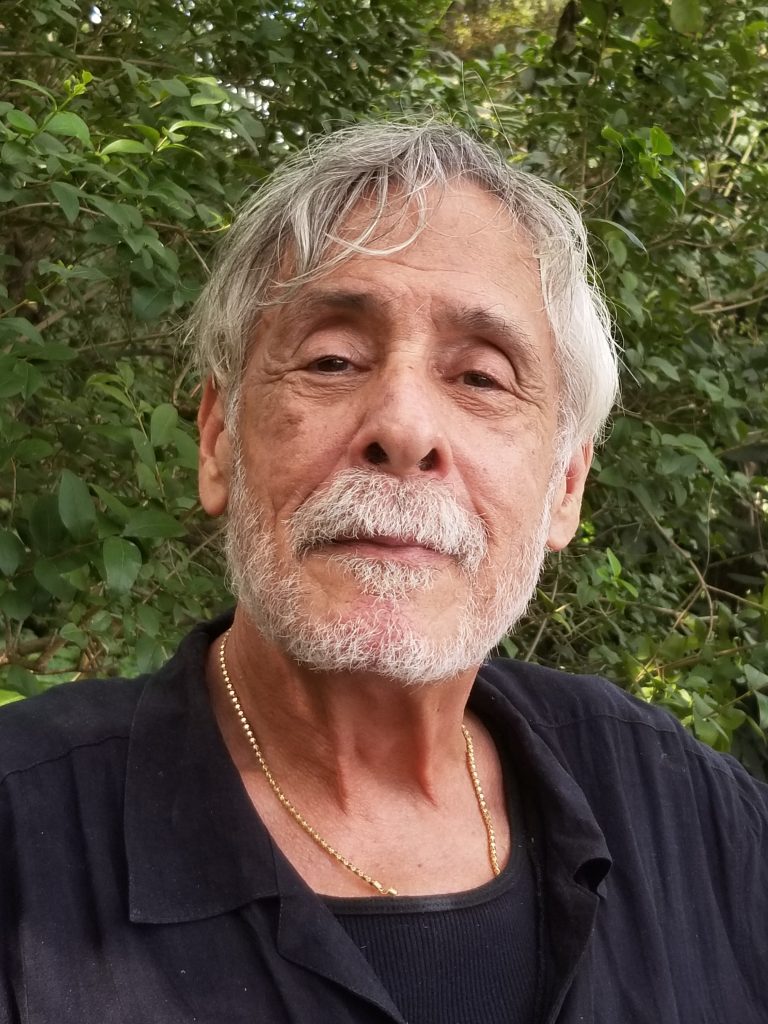

Photo credit: Hershey Felder Presents and Marco Badiani

Currently sitting out the plague in Florence, Italy, and itching for live theater to reopen, the ever-inventive Felder, not one to sit by doing nothing, decided to turn his widely praised solo-performed Tchaikovsky play – which premiered to rave reviews at the San Diego Repertory Theater in 2017 – into a full-length feature film.

Though the onset of Covid-19 darkened theaters around the world, not one to be silenced, the ever-spirited and extremely inventive Felder, currently sitting out the plague in Florence, Italy, decided to turn his solo-performed Tchaikovsky play – which premiered at the San Diego Repertory Theatre in 2017 – into a full-length feature film.

The end result being a beautifully crafted and directed (Hershey Felder and Trevor Hay), filmed and edited (Stefano Decarli and David Becheri), heart-felt love letter to both Tchaikovsky (1840-1893), the man and his music, and the city of Florence.

With Felder as Tchaikovsky and a cast of 15, most making cameo appearances to flesh out story, the film begins with the composer’s first movement of his Suite for Orchestra No. 1 in D Minor playing in the background, thus setting the elegiac tone of the film.

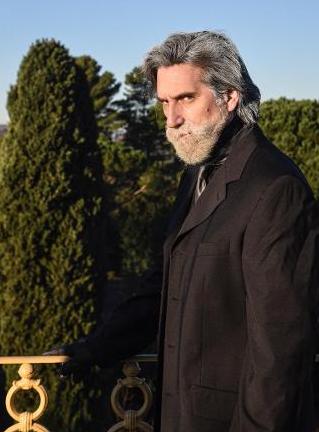

The year is 1878 and the 38-year-old, grey-bearded, silver and pepper-haired composer, having recently left St Petersburg to escape a disastrous marriage to a former student, and to quell rumors of his homosexuality is seen wandering along the streets of Florence. He appears to be deep in thought.

It might be, given what follows, that he is mentally composing a short note to his patroness Nadezhda von Meck (1831-1894) on whose largess he is currently living. At home, sitting at his desk with quill pen in hand – filmed at the very apartment where Tchaikovsky actually lived – he writes “My infinitely dearest friend, “I cannot express to you my charm of everything that surrounds me here. I love the character of Florence so much! And the knowledge that I am close to you.” At finish, carefully folding the note in quarters he tentatively presses it to his lips.

Nadezdha Filaretovna von Meck (Helen Farrell).

Photo credit: Hershey Felder Presents and Marco Badiani

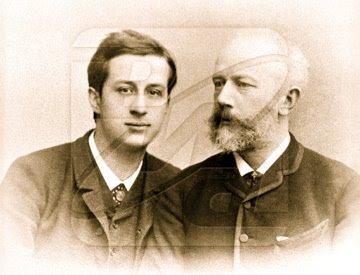

Though Tchaikovsky and von Meck exchanged over 1,200 letters between 1877 and 1890. As strange as it sounds, during their 13-year relationship, at von Meck’s request “that we must never see each other face to face,” they only met but once, and that accidentally in passing. In keeping to her wishes, no words were exchanged between them.

Leaving the film’s five-minute introductory hors d’oeuvre, we find ourselves catapulted 15 years into the future. The year is 1893 and we are at the home of Nikolai Borishovich Jacobi (Igor Polesitsky), a Senior Pubic Prosecutor and Tchaikovsky’s former classmate. The 53-year-old composer has been summoned to his home to explain a love letter that has written to a politician’s young son.

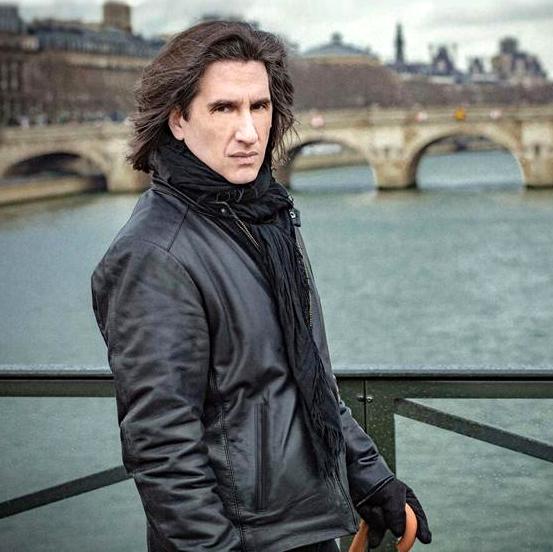

Photo credit: Hershey Felder Presents and Marco Badiani

With letter in hand Jacobi begins his interrogation. “What is this you’ve written a filthy little letter to and it has gotten into dangerous hands and now it’s not just your reputation is at risk but ours and your whole family your parents may they rest in peace. You know why you are here so begin at the beginning and tell us why.” For the next hour and forty-five finely scripted minutes, with much attention paid to Tchaikovsky’s innermost thoughts, his life is laid bare.

Further amplifying our experience, by cleverly matching Tchaikovsky’s music chronologically to each event being related by the composer, is classically trained Felder’s sumptuous piano playing. One cannot help but watch in awe as Felder’s long-tapered fingers, gliding passionately across the keys, perform passages from Romeo and Juliet, Piano Concert No. 1, Symphonies No. 4 (dedicated to von Meck), 5, and 6, The Nutcracker Suite, and the 1812 Overture, the latter Tchaikovsky’s least favorite composition. “It is loud and noisy and written without warmth or love,” he would frequently declare.

The film’s highly detailed story (credited to Meghan Maiya’s extensive research) takes us from the composer’s early years to a few days before his actual death in 1893. What did him in is still up for grabs. Did cholera, just like his mother’s own death, do him in? Did he commit suicide? Or was he murdered on orders from the Czar because of his sexuality? It is a mystery that may never be solved.

Photo credit: Hershey Felder Presents and Marco Badiani

Tchaikovsky’s life had its share of up and downs, and more than a few moments of depressive moments filled with despair. We hear about the loss of his mother at age 14. His discovery of his sexuality as a young boy. His days at various government schools. His professorship at the Moscow Conservatory, his three years of working in the Ministry of Justice, and his damnation by the more conservative and nationalist oriented Russian critics and composers who claimed that Tchaikovsky, given to pampering his audiences, was void of any talent.

Photo credit: Hershey Felder Presents and Marco Badiani

Worse was his wife’s continual threats to expose Tchaikovsky’s sexuality. Filled with fear of being sent to Siberia or worse, pay her he did, this despite her living with another man who fathered her 3 children.

Still, none of these troubling occurrences seemed to have kept the composer from churning out 7 symphonies, 11 operas, 3 ballets, 5 suites, 3 piano concertos, a violin concerto, 8 single movement orchestral works, 4 cantatas, 29 choral works, 3 string quartets, a string quartet, and more than 100 songs and piano pieces.

One of the major events in Tchaikovsky’s life – though often forgotten – was his 1891 trip to America. While he did visit Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington DC, and Niagara Falls, it was in New York City at the grand opening of Music Hall (soon to be known as Carnegie Hall) where he wowed both audience and critics for three days running. Though critics being critics they did take note of his “brusque and jerky bows.”

More than likely, this physical awkwardness, as Tchaikovsky himself wrote, was the result of his nine turbulent days at a sea on a steamboat where he had to endure terrible whether, irritating fellow passengers, the theft of his wallet, and the death of his sister just before he left Russia.

Loving America back, Tchaikovsky wrote to his nephew Vladimir “Bob” Davidov (1871-1906), a great love of his life, and perhaps even his lover at one point, “I am petted, honored and entertained here in every way possible. It turns out in America I am ten times more renowned than in Europe.” As was the case, he returned to Russia more famous than ever.

One of the film’s most moving scenes, of which there are many, comes close to the end of the film. Here, with tears streaming down Tchaikovsky’s face, and his Symphony No. 6 playing in the background, he delivers a painful, heart wrenching confession to his interrogator of his deep love for his nephew.

Photo credit is Hershey Felder Presents and Marco Badiani

“I dedicated my 6th Symphony to my beloved nephew. I’m in love with Bob,” he says, “because every time I look into this boy’s eyes, I can see that he understands who I am. This symphony the entire world will want to know what it means. But they can guess. But I know what it means. It is my conversation with this boy who is now twenty-one years old will finally understand what his life will be like.”

‘He may find love but he will not be able to celebrate it because he is like me,” he continues. “He will be frightened and he will feel so ashamed. So, this symphony is his because it is who we are. We are going to end in a whisper, No one is going to care about us. And just like the symphony we are going to fade away.” Little did he know that a century and a quarter later he would be still be firmly ensconced in the world’s top ten of the world’s most famous classical composers.

Though Felder, as the film’s creator, producer, director, and actor is the star of this film, hosanna’s also rest on the heads of Stefano Decarli and David Becheri, whose filming and editing keeps us glued to both Felder and the screen. Most effective is their use of sustained dissolves (layering) in which one element is placed over another – in this case the present over the past – so that we experience them separately and also together at the same time, thus allowing us to experiencing Tchaikovsky’s life in a kind of all-encompassing 3D effect.

The good news for the indefatigable Hershey Felder lovers is that he just released Before Fiddler, a film in which he plays Yiddish author and playwright Sholem Aleichem, the Ukraine-born author wrote more than 40 volumes of stories, novels and plays before his death in New York City in 1916. Aleichem’s most famous stories about Tevye the milkman was turned into the 1964 Broadway musical “Fiddler on the Roof.” Though it premiered live on February 7 it can also be accessed at www.HersheyFelder.net.

By Edward Rubin, Senior Associate Editor

Cast: Hershey Felder (Tchaikovsky), Nikolai Borishovich Jacobi (Igor Polesitsky, Senior Public Prosecutor), Helen Farrell, (Nadezdha Filaretovna von Meck), Trevor Hay (Modest Ilyich Tchaikovsky), Antonina Ivanovna Miliukova, (Marzia Sarti), Mama Tchaikovsky (Elia Nichols), Dario Rabitti (Young Tchaikovsky), Cosimo Francioni (Young Kireyev), Leone Pietrek (Young Bob), Stefano Decarli (Apukhtin), (Party Guests), Yves Besancon, Tomasso Betti, Erik Carstensen, Pierre Gerbe,Trevor Hay, Igor Polesitsky, Jeffrey Thickman

Technical: Production Design: Hershey Felder, Staging: Trevor Hay, Film Production and Live Editing: DeCarli Live Film Company, Live Broadcast and Sound Design: Erik Carstensen, Historical Research: Meghan Maiya, Original Tchaikovsky Costume: Abigal Gaywood, Costumes: Tedavi 98, Hair and Beard: Gherardo Filistrucchi, Wardrobe: Isabelle Gerbe, Director of I.T: Annette Nixon, Company Management: Samantha F. Voxakis