Picasso and the Guitar: Memory and Metaphor

Inspired by, ‘Picasso: Guitars (1912-14)’- At the Museum of Modern Art, New York City

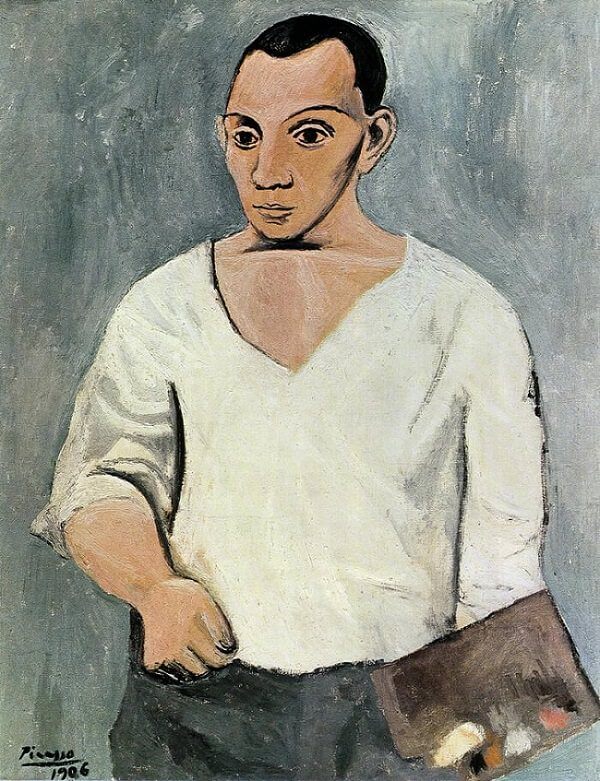

Though living in France most of his life, Picasso was a Spaniard, through-and-through, remaining proud of his birthright, cultural heritage and sun-drenched memories of childhood, over his lifetime. Any retrospective of his work as a painter and sculptor reveals that he was continually informed by the iconic images of Spain, at both conscious and unconscious levels: the raven-haired, large-eyed female figures, matadors and bull-fighting motifs, the open-balcony studio settings of his imagination, replete with palm-strewn vistas of warm seas, mythic creatures from Greco-Roman legend and seductive naked sylphs, all belie his enduring visceral attachment to las cosas de españa.

New York.

The Museum of Modern Art has in its permanent collection works by Picasso, focusing on two early collages (1912-14), where the guitar figures prominently as the central theme. This period represents Picasso’s formative years, when he was living in a cold-water Montmartre flat, befriending people who would later become the giants of 20th century arts and letters as he struggled to find his own creative voice in a radical climate of aesthetic reinterpretation. Experimenting with form and composition, subject matter and materials, Picasso’s unheated studio was an experimental laboratory for d’artes absurd. He had already produced his monumental painting, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), so rife with controversy for its stylistic bravado, fractured planes of color and ‘in-your-face’ social commentary, that it still lay propped in his studio—five years after its completion and viewed by only his closest allies—when he turned to a new medium.

Like his friend and fellow artist, Georg Braque, Picasso was intrigued by the use of everyday objects to make art: cardboard, newspaper, discarded sketches, theater broadsides, wallpaper and string. In 1912, he turned his creative attention to this new medium of collage (from the French, coller, for ‘glue’). Thematically, and even politically, the use of found objects to create art was intended to make a statement about the direction that art was taking at the time. With a break from past traditions, European culture was considering the impact of such modern innovations as the airplane, motorcar and assembly line production on the course of human history. The nations of Western Europe were also poised on the brink of another armed conflict—just how horrific—no one was yet to know.

So, Picasso gathered up scissors, knife and glue pot to produce serious art, even as the cultural ground was shifting beneath his feet. And what did he chose to create for the world’s first-ever sculptural collage?…a guitar. Deconstructed in a way that would become his signature Cubist style, unplayable and hardly recognizable to early 20th century eyes for what it was; it was, nevertheless, an interpretation of a classical guitar—known as the Spanish guitar—symbolic voice of his motherland . It must have evoked memories as he cut and pasted, placing pieces of cardboard and string into a loose configuration, resembling a musical instrument. The sights and sounds of his childhood in Barcelona and Seville surely filled his senses, as this 31-year old artist sat alone in his cold-water studio on the outskirts of Paris, cultural center of the world and the ‘City of Light,’ far from his true home. Picasso’s Guitar (1912) and the many other images of this instrument he was to produce in paper, on canvas and in prints, were not merely exercises in creativity, but served as a potent symbol of national identity and his indelible past—perhaps a very personal evocation of sensation and longing.

By Richard Friswell, Managing Editor

*Listen to the sounds of the Spanish guitar, a prominent subject in Picasso’s art, played by Andre Segovia in a live performance (circ. 1980) of Asturias (Leyenda), by Isaac Albeniz, on site at Alhambra, Seville, Spain